PETER PAN WEEK Day 5: Loss and Exclusion in Peter Pan

/Hey, folks! For the final of day "Peter Pan Week," we've got a special treat: Barrie scholar Kerry Mockler has written a post. Readers of The Scop might know Kerry better as "Kbryna," a regular commenter on this here blog and the woman behind The Moving Castle. Kerry wrote her master's thesis on The Little White Bird and is currently finishing a dissertation on Mr. Rogers at the University of Pittsburgh.[1. For those who have never been to Pittsburgh, it is worth noting that locals take their Fred Rogers very seriously.] Today she's agreed to share her thoughts about the most enigmatic character in all of Peter Pan ... the narrator! Take it away, Kerry:

* * *

We're used to thinking of Peter Pan as a symbol of perpetual childhood, of carefree innocence, joy, adventure, and freedom ... but Peter Pan also has nightmares. What we forget, or never knew in the first place, is that at its heart, all of Barrie's versions of Peter Pan are about loss and exclusion. That famous first sentence – "All children, except one, grow up" – sets up these themes, which also serve to close the novel. The loss of childhood (of one's own childhood and of one's child) finds expression throughout the novel, largely through the peculiarly ambivalent and enigmatic narrator. Exclusion and longing form -- for me, at least -- the strongest themes of the book, which make it one of the most melancholy stories I know. All those children, growing up, leaving behind Peter Pan who cannot grow up, and who masks his inability to grow up with the illusion of a defiant choice to remain a child.

Peter is not captain of the Neverland by choice, though he initially presents himself as an intentional runaway, defying the world that would have him grow up to be a man. Instead, he is marooned; when he tries to return to the home from which he has run away, "the window was barred, for mother had forgotten all about me, and there was another little boy sleeping in my bed." Thus he moves on to the Neverland, where he deals with lost children who all eventually outgrow their trees and their boy-leader. Peter's memory, a continual tabula rasa, prevents him from forming lasting relationships with anyone; even Tinker Bell, even Hook, are forgotten by the novel's end -- but the loss of that mother and that home are always with him.

The narrator of Peter Pan poses one of the biggest challenges to any reader; he attempts to identify with both child and adult, leaving us as readers in a linguistic and psychological muddle. The narrator’s inconsistency in using the first-person singular and first-person plural create confusion about his position in the text, and to whom he speaks: is he an adult addressing adults? or a child addressing adults? or an adult addressing both adults and children? He is never clearly one or the other, and never seems to manage to merge both into one adult/child hybrid; like Peter himself, the narrator is a "betwixt-and-between," neither one thing nor any other.[1. Upon returning to the Gardens in The Little White Bird, Peter is shocked to learn from the crow Solomon Caw that he is not still a bird, but more like a human — Solomon says he is crossed between them as a "Betwixt-and-Between."] The narrator's bitterness and unhappiness at his position is made clear at the end of the book, when the Darling children return home. Anticipating the reunion, the narrator says:

The narrator of Peter Pan poses one of the biggest challenges to any reader; he attempts to identify with both child and adult, leaving us as readers in a linguistic and psychological muddle. The narrator’s inconsistency in using the first-person singular and first-person plural create confusion about his position in the text, and to whom he speaks: is he an adult addressing adults? or a child addressing adults? or an adult addressing both adults and children? He is never clearly one or the other, and never seems to manage to merge both into one adult/child hybrid; like Peter himself, the narrator is a "betwixt-and-between," neither one thing nor any other.[1. Upon returning to the Gardens in The Little White Bird, Peter is shocked to learn from the crow Solomon Caw that he is not still a bird, but more like a human — Solomon says he is crossed between them as a "Betwixt-and-Between."] The narrator's bitterness and unhappiness at his position is made clear at the end of the book, when the Darling children return home. Anticipating the reunion, the narrator says:

"However, as we are here we may as well stay and look on. That is all we are, lookers-on. Nobody really wants us. So let us watch and say jaggy things, in the hope that some of them will hurt.”

The narrator’s exclusion from the homecoming scene echoes Peter’s exclusion from his own nursery. The narrator’s looking on from outside of the text recalls the image of Peter flying up to his old nursery window and finding it closed and barred. Watching the reunion of the Darlings, the narrator tells us:

“He had ecstasies innumerable that other children can never know; but he was looking through the window at the one joy from which he must be for ever barred."

Peter, of course, is not the only one to see the reunion; the narrator looks on as well and speaks for them both as he narrates the one joy from which both he and Peter are barred. As Hook and Mr. Darling are twinned, so too are Peter and the narrator. At the end, they are the only two who remain: Wendy grows up and Mrs. Darling dies, forgotten. The cycle of little girls to do the spring-cleaning goes on and on, but Peter and the narrator remain alone, excluded, untouched by time.

* * *

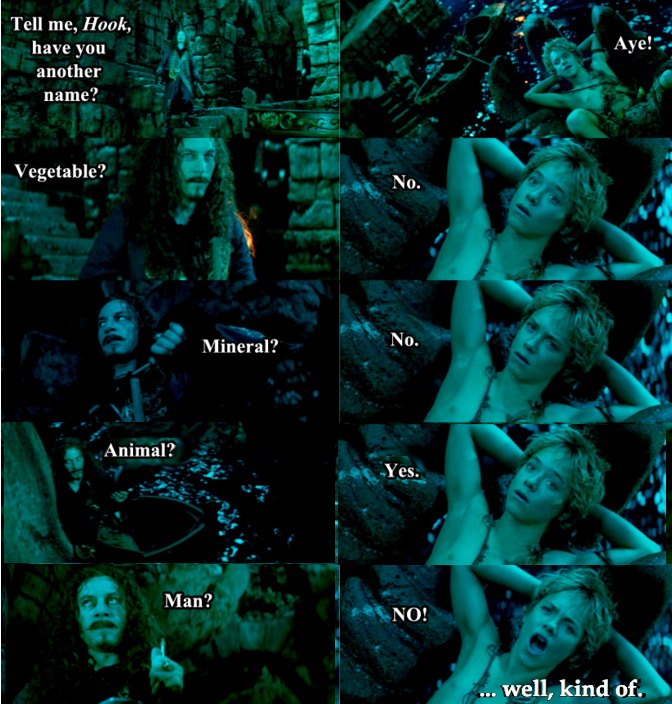

On that poignant note, we come to the end of "Peter Pan Week." While researching topics, I came across some great stuff I couldn't fit into posts -- including a few pretty hilarious Pan-related image macros, an incredibly disturbing headline, and a scathing review of Lars von Trier's offbeat movie adaptation. You should all count yourselves lucky that I didn't make it "Peter Pan MONTH." Now that would be an awfully big adventure.

For those who missed the other "Peter Pan Week" posts:

Day One: Literary Dress Rehearsals

Day Two: The Problem with Peter

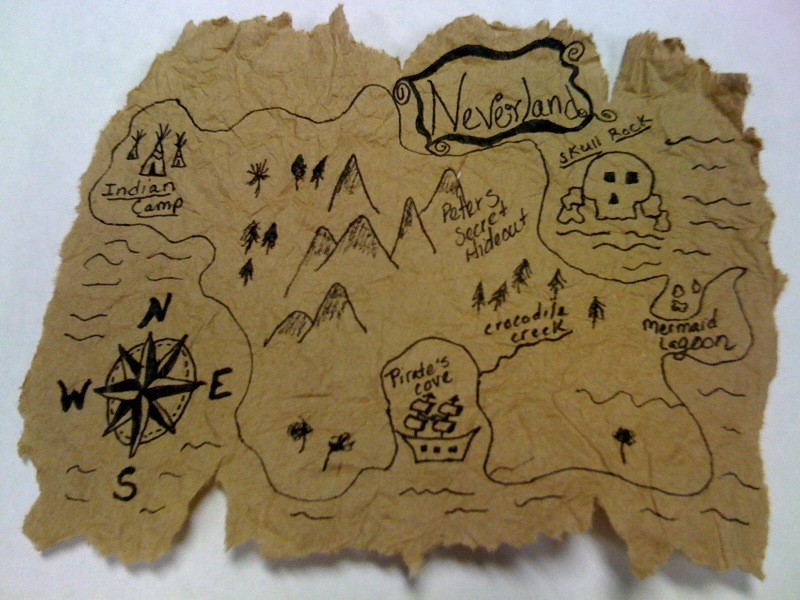

Day Three: Tink or Belle?

Day Four: The Neverland Connundrum

Also, you can also read my ham-fisted attempt to connect Peter Pan to The Hunger Games here.

As promised

As promised