Last week for our Children's Literature course, we had an enjoyable discussion about Roald Dahl's Matilda. This book is very dear to me -- it was the first "long" book I read as a child and it sparked a lifelong love of reading. One thing that struck me during our conversation was how many things in this book run contrary to current parenting trends. Let's dive right in ...

1) Let them Read Anything

More than a few children's books include reading lists of all the novels the protagonist loves. This usually functions as a sort of literary name-dropping intended to give a young hero instant credibility with readers: "You loved the Narnia books and so did my main character!" With Dahl's book, however, it's a little different. He doesn't just have Matilda read beloved children's books, he has her read beloved adult books -- the list includes Dickens, Bronte, Hardy, Hemingway, Greene, Orwell, and Faulkner among others. Most of the titles are ones that would get a parent arrested for showing to their child. Tess of the D'Urbervilles? Really? Dahl doesn't even let us pretend that young Matilda skipped over the dirty bits; he makes the point of including a scene where the girl asks her librarian about Hemingway's sex scenes. What's the woman's response? "Don't worry about the bits you can't understand. Sit back and allow the words to wash around you, like music."

More than a few children's books include reading lists of all the novels the protagonist loves. This usually functions as a sort of literary name-dropping intended to give a young hero instant credibility with readers: "You loved the Narnia books and so did my main character!" With Dahl's book, however, it's a little different. He doesn't just have Matilda read beloved children's books, he has her read beloved adult books -- the list includes Dickens, Bronte, Hardy, Hemingway, Greene, Orwell, and Faulkner among others. Most of the titles are ones that would get a parent arrested for showing to their child. Tess of the D'Urbervilles? Really? Dahl doesn't even let us pretend that young Matilda skipped over the dirty bits; he makes the point of including a scene where the girl asks her librarian about Hemingway's sex scenes. What's the woman's response? "Don't worry about the bits you can't understand. Sit back and allow the words to wash around you, like music."

2) Give them a Long Leash

Kids today can't go anywhere without their parents knowing. Yes, a cell phone is a form of freedom, but it is also a way for a parent to track their children's every move. Newbery winner Rebecca Stead has stated that she set When You Reach Me in the 70s because kids today don't have the independence necessary for her story. I'm sure Roald Dahl would agree. While re-reading Matilda, I noticed how he makes a point of letting his young hero do grown-up things. The whole story starts with her walking to the library by herself at four years old. And this isn't just parental negligence. The first thing the kind Miss Honey does when she invites Matilda into her house is ask the girl to fetch some water: "The well is out at the back. Take the bucket on the to the end of the rope and lower it down, but don't fall in yourself." When's the last time you heard a parent tell their child to make herself useful and do something that could kill them?

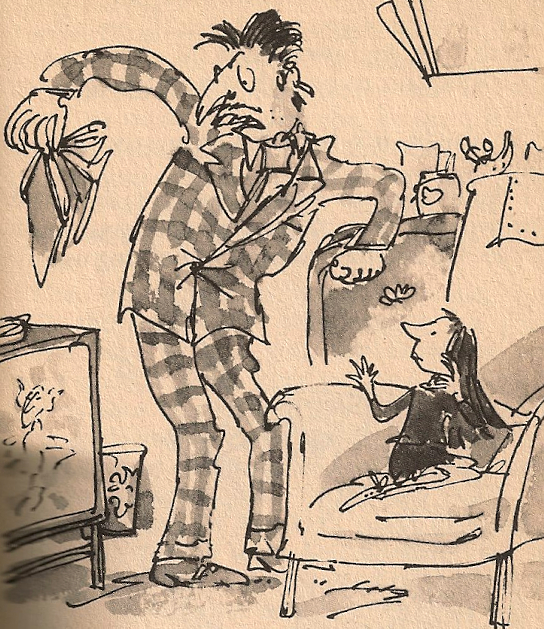

3) No Positive Reinforcement

The book opens with an authorial screed about parents who dote too much on their children. Dahl fantasizes about being a teacher and sending home more accurate letters describing his students: "Your son Maximilian ... is a total wash-out. I hope you have a family business you can push him into when he leaves school because he sure as heck won't be getting a job anywhere else." Later on in the story, the lovely Miss Honey bemoans how parents are constantly over-praising and over-estimating their mediocre children. And even after Matilda reveals herself to have psychic powers, Miss Honey is careful not to let her get a big head. "It is quite possible that you are [a phenomenon] ... But I'd rather you didn't think about yourself as anything in particular at the moment." This runs contrary to the current trend of telling every kid that they can become an astronaut or the president.[1. By my last count, only 1 in 300,000,000 people gets to be the president -- chances are you're kid's not it.]

4) Blood is Bad

Dahl doesn't play the coward by giving Matilda evil step-parents or evil guardians. She has evil parents. Period. In doing this, Dahl breaks the tradition of letting adult readers delude themselves into thinking that they could never do the horrible things that book villains do.[2. I have to give a shoutout to Betsy Bird for making this same observation last year in her Top 100 Children's Books series.] It also dispels the fantasy that being related to a person necessarily means you will be loved by them. This is a narrative conceit that has bothered me in countless movies/books/sitcoms, and I'm always glad to see it challenged -- It's the reason I prefer "Hansel & Gretel" to "Cinderella."

Dahl doesn't play the coward by giving Matilda evil step-parents or evil guardians. She has evil parents. Period. In doing this, Dahl breaks the tradition of letting adult readers delude themselves into thinking that they could never do the horrible things that book villains do.[2. I have to give a shoutout to Betsy Bird for making this same observation last year in her Top 100 Children's Books series.] It also dispels the fantasy that being related to a person necessarily means you will be loved by them. This is a narrative conceit that has bothered me in countless movies/books/sitcoms, and I'm always glad to see it challenged -- It's the reason I prefer "Hansel & Gretel" to "Cinderella."

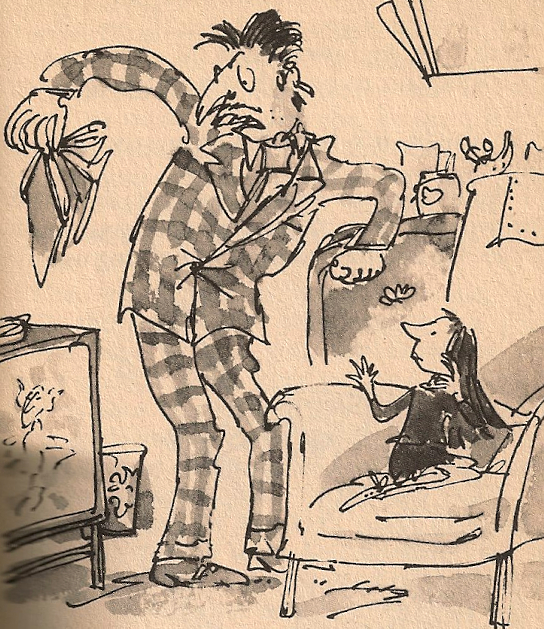

5) Golden Rule, Shmolden Rule

There is a central cruelty to this novel that I think makes it unique among children's books. Wronged kids are nothing new in children's literature, but Dickens never let Oliver Twist come back and terrorize his persecutors. Matilda, on the other hand, dishes out revenge with gleeful pettiness. Consider her first strike against Mr Wormwood: he demands that she eat dinner in the living room, and so she puts superglue in his hair. That's draconian by any standard. Dahl knows it, too, and he complicates the book by blurring the line between Matilda and Trunchbull -- consider how both characters always make sure the punishment fits the crime.[3. This is actually a subject big enough for its own post -- I think the subtle differences between Matilda and Trunchbull set up a very sophisticated set of moral rules that determine who deserves punishment. My guess on the deal-breaker? Bad sportsmanship.] This connects to a thread that runs through all Dahl's best work -- revealing how children can be just as cruel and selfish as the worst adults.

There is a central cruelty to this novel that I think makes it unique among children's books. Wronged kids are nothing new in children's literature, but Dickens never let Oliver Twist come back and terrorize his persecutors. Matilda, on the other hand, dishes out revenge with gleeful pettiness. Consider her first strike against Mr Wormwood: he demands that she eat dinner in the living room, and so she puts superglue in his hair. That's draconian by any standard. Dahl knows it, too, and he complicates the book by blurring the line between Matilda and Trunchbull -- consider how both characters always make sure the punishment fits the crime.[3. This is actually a subject big enough for its own post -- I think the subtle differences between Matilda and Trunchbull set up a very sophisticated set of moral rules that determine who deserves punishment. My guess on the deal-breaker? Bad sportsmanship.] This connects to a thread that runs through all Dahl's best work -- revealing how children can be just as cruel and selfish as the worst adults.

Just a few bits of child-rearing wisdom from old Uncle Roald. So throw away your Baby Einstein, pull out the TV dinners, and get parenting!

* * *

In two weeks, I'll be discussing Melina Marchetta's Jellicoe Road. For those interested, you should check out these other posts from our course reading list:

Plot vs. Story in The Chocolate War

Realism and talking Pigs in Winnie-the-Pooh and Charlotte’s Web

Literary dress rehearsals in Peter Pan

On the shoulders of A Little Princess

The childlit mentor in The Coral Island

How Little Goody Two-Shoes influenced other major children's books.