THE CHOCOLATE WARS Quote #1

/From Chapter One: "The coach looked like an old gangster: broken nose, a scar on his cheek like a stitched shoestring. He needed a shave, his stubble like slivers of ice."

- Robert Cormier The Chocolate Wars

From Chapter One: "The coach looked like an old gangster: broken nose, a scar on his cheek like a stitched shoestring. He needed a shave, his stubble like slivers of ice."

- Robert Cormier The Chocolate Wars

Hey, readers! I have a quick, exciting announcement about the forthcoming book: Abrams is letting me illustrate! The good news is that I'm going to start posting drawings-in-progress and some other Peter Nimble-related tidbits in the coming weeks. The bad news is that I'm on a tight deadline, which will be eating into my regular blogging schedule. I'll still be posting at least twice a week, but I need to make a little extra time for drawing! More to come ...

While going over Peter Nimble proofs with my editor, I came across the term "interrobang," which is the name for a combined question mark and exclamation point ("?!"). In the 1960s, some typeface smartypants even tried making it into a single character:

Earlier today the children's book world was squirming in unison from a tweet sent by Jennifer Laughran. It was a link to a Wikipedia article about something called a "rat king." Rat kings are clusters of rats whose tails have become intertwined -- either with blood, excrement, dirt, or plain-old tangling. Apparently they continue to live in these large co-joined packs for quite some time. The Wikipedia article features a photo of a mummified rat king which is pretty disgusting. I warned Mary not to click on the link, but she could not resist. She saw the page for all of half-a-second before screaming and almost dropping her computer. When she looked up again, I was already hunched over my journal, drawing away:

Don't be surprised if one of these things ends up in a book of mine one day. You have been warned.

Don't be surprised if one of these things ends up in a book of mine one day. You have been warned.

This weekend I sat down to write my dedication for Peter Nimble. This is something I have mulled over quite a bit in the last few years. Like naming my (imaginary) boat or drawing my (non-existant) tattoo, wording my first dedication was a flight of fancy. When my editor told to submit something by Monday, I completely clammed up. The fantasy had become a reality, and I was terrified of blowing it. Should I write something intimate and cryptic? Something sweet and funny? Something in keeping with the tone of the book? Of course, it doesn't really matter to a reader what I write. Readers are interested in the story, not in a few words opposite the copyright page. But every once in a while, I see a dedication that makes a book come alive -- something that makes me long to know the author personally, and slightly jealous of the lucky dedicatee.[1. Bet you didn't think that was a word.] With the spectre of those great dedications in mind, I started browsing my bookshelf, thumbing through examples that really stuck in my memory. Here are a few of my favorites:

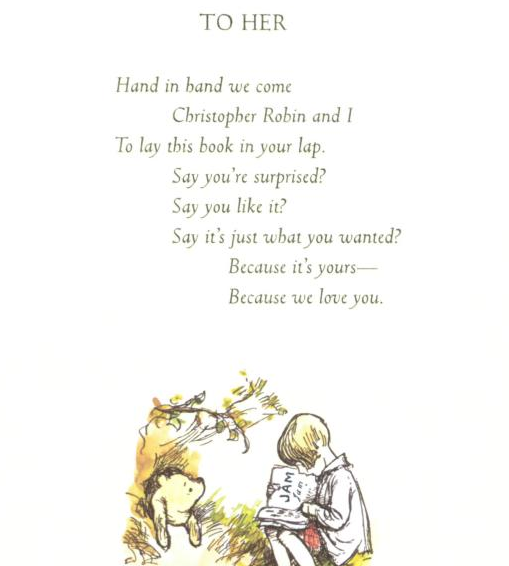

As I've mentioned before, this whole book is adorable from start to finish. The dedication is no exception ...

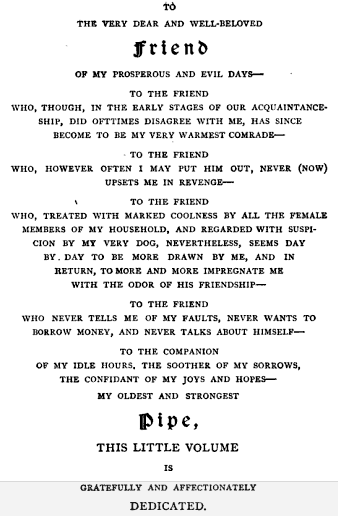

So far as I'm concerned, Jerome does not get his due. He is a truly funny writer, as exhibited by this delightful dedication to his beloved pipe ...

So far as I'm concerned, Jerome does not get his due. He is a truly funny writer, as exhibited by this delightful dedication to his beloved pipe ...

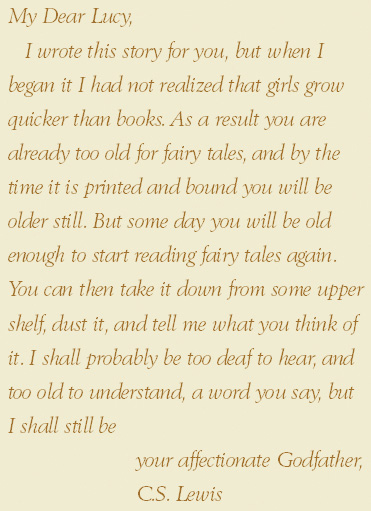

I'm not the biggest fan of this installment of the Narnia series (more of a Magician's Nephew kind of guy), but the dedication at the front is hard not to love.[2. Unless you're Philip Pullman, that is.]

This is a long poem written for Chesterton's childhood friend, Edmund Clerihew Bentley. I think Chesterton is someone best taken in small doses, which would explain why this dedication is better than the book itself!

This is a long poem written for Chesterton's childhood friend, Edmund Clerihew Bentley. I think Chesterton is someone best taken in small doses, which would explain why this dedication is better than the book itself!

And finally comes this newer edition to the canon of great dedications, which made me laugh out loud in the bookstore:

For those interested in reading more about dedications, there's an essay collection called Once Again to Zelda that tells the story being fifty famous dedications; the book got mixed reviews, but still might be worth checking out. Also, feel free to put down your own favorite literary dedications in the comments section.

As for what I wrote in Peter Nimble? You'll have to wait and see.

UPDATE: readers chimed in with their own favorite dedications here.

New feature! Recently, a few people have been contacting me with questions about various aspects of publishing or writing craft. I'm well aware that there is no shortage of websites devoted to answering publishing questions (most of them written by people far smarter and more qualified than myself). Still, I thought it might be worth adding my drop into the bucket from time to time.

* * *

I was wondering how you feel about literary contests for unpublished authors that require and entry fee of $25- $50 with the promise of a rather large money prize and/or publication? I am having trouble finding contests that are free.

I was wondering how you feel about literary contests for unpublished authors that require and entry fee of $25- $50 with the promise of a rather large money prize and/or publication? I am having trouble finding contests that are free. This is an excellent question. First off, I should warn you that my experience with contests is pretty much limited to the screenwriting world. The short answer is that I'm a big believer in writing competitions. They are an opportunity not only to possibly generate some interest from seemingly-unreachable gatekeepers but also to help young writers gain confidence and professionalize themselves. After being forced to write a million plot summaries for my scripts (all of different length, of course), I started to get a good sense of how to pitch my story ... and some of that insight even helped inform rewrites. I finally did win some contests and fellowships, which helped finance my move out to Los Angeles. Once here, the prize money afforded me the time to write scripts ... which I then submitted to competitions. Eventually, one of those scripts made "semi-finalist" in a major competition. There was no prize, but even placing was enough to attract the attention of managers.[1. I should say that while waiting to hear back from competitions, I was also writing new scripts and building relationships with people in TV and film -- winning a contest got my manager to call, but it was this other work that made him willing to sign me.]

This is an excellent question. First off, I should warn you that my experience with contests is pretty much limited to the screenwriting world. The short answer is that I'm a big believer in writing competitions. They are an opportunity not only to possibly generate some interest from seemingly-unreachable gatekeepers but also to help young writers gain confidence and professionalize themselves. After being forced to write a million plot summaries for my scripts (all of different length, of course), I started to get a good sense of how to pitch my story ... and some of that insight even helped inform rewrites. I finally did win some contests and fellowships, which helped finance my move out to Los Angeles. Once here, the prize money afforded me the time to write scripts ... which I then submitted to competitions. Eventually, one of those scripts made "semi-finalist" in a major competition. There was no prize, but even placing was enough to attract the attention of managers.[1. I should say that while waiting to hear back from competitions, I was also writing new scripts and building relationships with people in TV and film -- winning a contest got my manager to call, but it was this other work that made him willing to sign me.]As to your entry fee question, I'd say it depends. Reading and sorting thousands of entries is a huge endeavor, and I don't begrudge the organizers for wanting to fund the operation. The problems start when the exchange is less cut-and-dry. I know a lot of fiction contests offer some kind publication as a prize. In general I would say avoid contests that come with contractual obligation. To my thinking, if you're paying $30-$50 bucks to enter then the prize should be cash (and recognition) ... otherwise it feels dangerously close to you paying a publisher to publish your book. Still, I know fiction is a tough racket to break into, and taking a lowball publishing deal might be worth if for you if it means getting your foot through the door.

Screenwriter John August has a number of valuable posts on the subject of screenwriting contests. On the fiction side, Nathan Bransford does a good job summing up the issue. Poets & Writers magazine has a nice database of competitions and grants, and, of course, always check out Writer Beware's section on contests before sending anyone money. Hope that helps!

In the coming weeks, I'll try to post my responses to some other questions. If you've got anything you want me to answer, feel free to send me an email by clicking on the adorable little envelope:

In the coming weeks, I'll try to post my responses to some other questions. If you've got anything you want me to answer, feel free to send me an email by clicking on the adorable little envelope:Today we've got a post from friend and booklover Craig Chapman. Readers of The Scop might recognize his name from the comments section. Back in high school, Craig and I regularly cleaned up in the local debate scene. Look! Here we are in our school year book:

Nowadays, Craig is some kind of mad scientist, but in his spare time he reads a lot of YA. Recently, he was talking to me about China Mieville's YA fantasy, Un Lun Dun. I only know Mieville as the guy who hates Tolkien, but apparently his book made some waves as a sort of anti-Harry Potter. I asked Craig to share some of his thoughts on the blog, and boy did he deliver! Please forgive his ridiculous Canadian spellings ...

Nowadays, Craig is some kind of mad scientist, but in his spare time he reads a lot of YA. Recently, he was talking to me about China Mieville's YA fantasy, Un Lun Dun. I only know Mieville as the guy who hates Tolkien, but apparently his book made some waves as a sort of anti-Harry Potter. I asked Craig to share some of his thoughts on the blog, and boy did he deliver! Please forgive his ridiculous Canadian spellings ...

* * *

Conventions can be liberating. They establish expectations that convey volumes of information. Taking an example from my world of research in behavioural neuroscience, humans have the unique ability to accurately guess what another person is thinking. This ability – referred to as Theory of Mind – is thought to be the base capacity required for successful communication. Here’s an example: You are walking by the office of a co-worker and see that they are looking frustrated while rummaging through an open drawer. You infer that this person is looking for something. Of course, it is possible -- though unlikely -- that they are trying some new exercise regimen. How do you know that the first option, if not correct, is much more likely? The simple answer is that it fits with the context. That is, given the surroundings, your experience with this person, their expression, and even thinking how you might act in the same situation, you expect that they are looking for something. And so you ask “What are you looking for?” instead of “How many calories have you burned”?

Along the same lines, authors can use conventions to convey information without the need to write anything down. Consider a recent post and comments on this blog regarding the ‘Childlit mentor’. It went without saying that we all knew exactly what a mentor was like. They are old, and wise. They help the protagonist when all seems lost, or when things just don’t make sense. By using a convention like the mentor, the author gets all of this content for free. I don’t think I’d even ‘met’ Dumbledore as a reader and I already knew that he was the key to a lot of the challenges Harry would face (and that he was probably an awesome wizard, too!).

Of course, the problem of relying on conventions is that they can become stale – the text that overuses them can feel derivative and ultimately boring.[1. One personal pet peeve is how unimaginative fantasy authors are when conceptualizing how magic might work. Almost always magic is simply the act of thinking really hard, then saying a word (the ‘Force’, the ‘Will and the Word’, ‘Avada Kedavra’ etc.).] Of course an author can decorate convention, dress it up so it seems new or interesting to explore because of its dressing. For the perfect example, you need look no further than Harry Potter. Rowling relies heavily on convention, but gives such exquisite details that it becomes a joy to read what could otherwise have come off as “more of the same.” Still, there is a reason why not everyone is a Rowling: making old conventions novel is ultimately very difficult.

Given the risks associated with over-used tropes, why don’t we read more books that are completely unconventional? The problem is this: if you create something truly new you have to spend a significant amount of text describing how this new thing works. And in doing so you risk losing your reader. Moreover, when a reader fills in the blanks of a story employing a particular convention, they will likely fill those blanks with material that they like. While we might all know what a mentor is, your mentor and my mentor might be different – but as long as the author leaves it to the reader to fill in the details, then each of us can use whatever mentor we like best.

Perhaps there is therefore good reason why we don’t see many examples of true unconvention – because largely it doesn’t work, at least not for a broad readership. But occasionally, I have seen excellent examples of authors being unconventional. In his book Un Lun Dun, China Mieville employs the tactic of anti-convention.[2. Mieville also writes some of the best adult sci-fi/fantasy I have ever read; his book Perdido Street Station is so incredibly imaginative and horrific that it literally gave me nightmares, and his book The Scar (my personal favorite) has the single most memorable image I've ever seen, heard, or read in any medium.] He doesn’t create something new, but rather he uses the exact opposite of a whole host of conventions:

Perhaps there is therefore good reason why we don’t see many examples of true unconvention – because largely it doesn’t work, at least not for a broad readership. But occasionally, I have seen excellent examples of authors being unconventional. In his book Un Lun Dun, China Mieville employs the tactic of anti-convention.[2. Mieville also writes some of the best adult sci-fi/fantasy I have ever read; his book Perdido Street Station is so incredibly imaginative and horrific that it literally gave me nightmares, and his book The Scar (my personal favorite) has the single most memorable image I've ever seen, heard, or read in any medium.] He doesn’t create something new, but rather he uses the exact opposite of a whole host of conventions:

START SPOILER ALERT!

In the book, the Chosen-One is a beautiful blond girl who shoulders her fate with quiet resolve -- but she goes down early and it’s her tag-along, rather-plain friend Deeba who becomes the hero of the story. The prophecy describing how to defeat the evil Smog is spoken by a book, guarded by a sect of wise “Propheseers” -- all of which turn out to be hopelessly false ... not malicious, just wrong. Deeba’s sidekick is a milk carton named Curdle who in the final fight cowers in the corner and at no point does anything to save the hero. And, my personal favourite, when Deeba is faced with completing seven tasks to find seven essential tokens, she decides there is no time and completes the seventh task first, thus acquiring the most essential item (the UnGun, which, as you might guess, works best when firing nothing).

END SPOILER ALERT.

It ends up being a fun exercise to consider all the ways Mieville plays with anti-convention from the title through to the end of the book. It’s almost as much fun to consider whether all of the unconventions are meant to specifically mirror Harry Potter or not.

By using anti-convention, Mieveille still gets all the free content that comes with the expectations associated with conventions. Then, by turning a convention on its head, he makes the unconvention new and interesting for the reader. Ultimately, Mieville is playing a complex game using Theory of Mind. He supposes that his reader will have a whole host of beliefs and expectations that come from the conventions he employs. But more than that, he wagers that he can guess almost the exact content of your beliefs and then invert them; the result runs so counter to what you expected that it is enjoyable.

By using anti-convention, Mieveille still gets all the free content that comes with the expectations associated with conventions. Then, by turning a convention on its head, he makes the unconvention new and interesting for the reader. Ultimately, Mieville is playing a complex game using Theory of Mind. He supposes that his reader will have a whole host of beliefs and expectations that come from the conventions he employs. But more than that, he wagers that he can guess almost the exact content of your beliefs and then invert them; the result runs so counter to what you expected that it is enjoyable.

It’s as though he’s guessing that when I’m reaching in my drawer I’m looking for something, then deliberately asks me how many calories I’ve burned, knowing that I’ll get the joke.

Today I thought I'd talk about the last couple of books Mary and I have been discussing in our Children's Literature class. We rounded up the first half of our semester with a few books about animals -- specifically, Winnie the Pooh, Charlotte's Webb, and A Day No Pigs Would Die.

Winnie-the-Pooh by A.A. Milne

This book marked a change from previous texts in the course. While still being British, Pooh has very little to do with colonialism or moral instruction. Instead it's just a great big exercise in adorableness. "How adorable," you ask? I defy you to read this page and not smile.

This book marked a change from previous texts in the course. While still being British, Pooh has very little to do with colonialism or moral instruction. Instead it's just a great big exercise in adorableness. "How adorable," you ask? I defy you to read this page and not smile.

I once had a friend observe that -- other than the wind -- Winnie-the-Pooh is an adventure without an antagonist. I think that's by design. There's a lot to be said about the fact that this book was published in the shadow of World War I. It's a safe bet that most of Milne's readers were the children of veterans, and I can imagine those parents embracing the idea that their progeny were somehow too innately good to ever march into war. In this way it sort of acts as a critique for the bloody adventures of a Peter Pan or Rover Ralph -- whereas those characters romanticize violence, Christopher Robin illuminates the beauty of real-life child's play.

Charlotte's Web by E.B. White

I think there's some interesting stuff in the gap between Pooh and Charlotte's Web. Like the previous novel, this, too, was written after a World War -- but it was a bigger war that changed the landscape in even more terrifying ways. It's one thing to indulge in a little escapism after fighting the Kaiser, but doing so after Hitler and "The Bomb" somehow feels like poor taste. Instead White gives us a book full of compassion -- but not so much that it ignores the reality of death.

I think there's some interesting stuff in the gap between Pooh and Charlotte's Web. Like the previous novel, this, too, was written after a World War -- but it was a bigger war that changed the landscape in even more terrifying ways. It's one thing to indulge in a little escapism after fighting the Kaiser, but doing so after Hitler and "The Bomb" somehow feels like poor taste. Instead White gives us a book full of compassion -- but not so much that it ignores the reality of death.

"Hang on," you might be saying. "If Charlotte's Web is aiming for 'reality,' why all the talking animals?" I think White knew that the impact of animal deaths would only land if we cared for them as we would humans -- which he could only do by making them talk. Through fantasy, White makes his story feel realer than real-life. If you ask me, that's a pretty neat trick.

A Day No Pigs would Die by Robert Newton Peck

This third book wasn't one we could fit into the course for time-reasons. That's a pity because A Day No Pigs Would Die is a truly wonderful book that doesn't get its due. It's pretty much the exact same story from Charlotte's Web, but now all bits of fantasy have been stripped away -- including the fantasy that a farm animal can avoid death. It is a profoundly-moving book about a Shaker boy and his doomed pet.

This third book wasn't one we could fit into the course for time-reasons. That's a pity because A Day No Pigs Would Die is a truly wonderful book that doesn't get its due. It's pretty much the exact same story from Charlotte's Web, but now all bits of fantasy have been stripped away -- including the fantasy that a farm animal can avoid death. It is a profoundly-moving book about a Shaker boy and his doomed pet.

I first became aware of Day when I taught reading classes to middle-schoolers. Anyone who's taught that age knows that they can be a pretty jaded group -- add to this the fact that this was a summer class that my students were being forced to addend and you've got a pretty hostile audience. This book changed all that. Students read and discussed the novel over the course of a week, and on the final day, I read the last chapter aloud to them ... without fail, every kid in the room was a sobbing mess. Awesome.

So that ends the first half of our semester! Later in the week, I'll unveil the next chunk of books, which will take us into the scary land of YA. Until then!

Yesterday Mary was looking up the origins of the word "quiz" -- specifically wanting to know at what point it became a verb related to testing.[1. It originally meant "an odd or eccentric person in character or appearance" (OED).] Her research led to this 18th century quote: "Everybody seems to set me down as a butt made on purpose to be ridiculed ... as if I had 'This man is quizable' pasted in large letters upon my back."[2. From The Quiz No. 13. (1797).]

Nice to know that some things never change ...

Nice to know that some things never change ...

The protagonist on his fighting parents: "I shut my door and push a chair against it, then duck for cover under my blanket. Still, it feels like every shot they take at each other passes through me first."

- Lisa Yee Stanford Wong Flunks Big Time

Anyone who knows me knows that I always carry a black, spiral-bound journal under one arm. It's full of things I've seen and read -- if you say something really witty at a party, I might just open up the book and write it down.[1. Over the years, I've developed a complicated system of symbols to indicate attribution of ideas so that I don't accidentally use someone else's original ideas in my own writing.] I know some writers treat their notebooks like pieces of art, but that's never really worked for me -- I need something fast and functional.

It took me years to find a journal that was the right size and weight, and once I finally got something, I stuck with it.[2. I know a lot of people gush about Moleskine notebooks, but I can't draw in something with a closed binding.] I've been using the same model notebook and pen for over ten years now. The first time I sold a piece of art, I used all the money to buy a reserve supply of both, just in case the manufacturers went out of business!

Anyone who knows me knows that I always carry a black, spiral-bound journal under one arm. It's full of things I've seen and read -- if you say something really witty at a party, I might just open up the book and write it down.[1. Over the years, I've developed a complicated system of symbols to indicate attribution of ideas so that I don't accidentally use someone else's original ideas in my own writing.] I know some writers treat their notebooks like pieces of art, but that's never really worked for me -- I need something fast and functional.

It took me years to find a journal that was the right size and weight, and once I finally got something, I stuck with it.[2. I know a lot of people gush about Moleskine notebooks, but I can't draw in something with a closed binding.] I've been using the same model notebook and pen for over ten years now. The first time I sold a piece of art, I used all the money to buy a reserve supply of both, just in case the manufacturers went out of business!

Wanna see what's inside these magical pages? To do that, you'll have to mosey on over to The Reading Zone where Sarah Mulhern has collected images from a bunch of different authors' notebooks -- including mine.[3. Sarah is just one of many bloggers working to promote literacy in a gigantic blogging event called Share a Story - Shape a Future.] Among the photos in her post, you'll find a rough sketch illustrating my second-favorite Roald Dahl scene ... one million blog points to whoever can guess the picture in advance!

From Chapter One: "Allow me to warn you now that, under any other circumstances, stealing a girl is about the worst way of winning her heart you could possibly cook up. ... But because this happened long ago, in a faraway land, it seems to have worked."

- Adam Gidwitz A Tale Dark and Grimm

Today is the third day of Share a Story – Shape a Future 2011, an internet superfest designed to promote literacy. Each day this week bloggers all over the world will write on a specific topic -- today's topic is “Unwrapping Literacy 2.0.” Now I've already written a bit about the pros and cons of e-books from a publishing angle, so today I thought I'd discuss things from a young reader perspective. But first, a little background on reading development ...

Today is the third day of Share a Story – Shape a Future 2011, an internet superfest designed to promote literacy. Each day this week bloggers all over the world will write on a specific topic -- today's topic is “Unwrapping Literacy 2.0.” Now I've already written a bit about the pros and cons of e-books from a publishing angle, so today I thought I'd discuss things from a young reader perspective. But first, a little background on reading development ...

When I finished grad school, I took a job as a reading teacher for a company called the Institute of Reading Development. Our curricula were modeled after Dr. Jeanne Chall's stages of reading development. Each stage is fascinating and worthy of discussion, but today I want to focus on stage two: "Confirmation & Fluency."

This stage usually spans the 2nd and 3rd grades -- just after readers have mastered phonetics and can now read silently. During these years, their primary mission is exposure: kids simply need to see as many words as possible so that their sight vocabulary can grow to match their spoken vocabulary. If reading development were a video game, stage two would be nothing but grinding.

This stage usually spans the 2nd and 3rd grades -- just after readers have mastered phonetics and can now read silently. During these years, their primary mission is exposure: kids simply need to see as many words as possible so that their sight vocabulary can grow to match their spoken vocabulary. If reading development were a video game, stage two would be nothing but grinding.

The books children read during this phase are specifically designed to let the brain go on autopilot. They often feature simplistic characters and repetitive plots -- think of The Hardy Boys or Nancy Drew. These are sprawling series books that could be read in any order because, ultimately, nothing ever happens in them.[1. To hear me dump on more of your childhood, click here.] And that's okay; such books provide an essential service to young readers: they deliver a massive amount of unchallenging yet engaging content that equips readers to move on.

These kinds of books remind me of something Neil Gaiman said at ALA in January about parenting: "It's odd, because you spend all this time creating this brilliant, fascinating person ... and if you've done your job right, at the end of eighteen years they leave you."[2. My notes from ALA were particularly scribbly, so this is actually more of a reconstruction than direct quote.] Similarly, if stage two books have succeeded, then a reader need never go back to them -- and if they do decide to return, they might not like what they find.[3. Thanks to Betsy Bird for the link!]

I think it's appropriate that so many of these series books are mysteries. Mysteries are, by and large, not much fun to read once you know whodunit. Put the two things together and you've got a perfect marriage between form and function.

I think it's appropriate that so many of these series books are mysteries. Mysteries are, by and large, not much fun to read once you know whodunit. Put the two things together and you've got a perfect marriage between form and function.

So what does all this have to do with "Unlocking Literacy 2.0?" Well, I tend to wonder whether an e-reader is a perfect device for disposable books -- especially if young readers are able to pay for a subscription service that gives them access to all the Magic Tree House (or Tom Swift or Goosebumps or Boxcar Children) they can handle without burdening them with the physical remainder.

Then again, what's the fun of reading a book if you can't put it on the shelf when you're done?

* * *

That's it for me. If you want to read more about Literacy 2.0, go visit Danielle Smith at There's a Book.

As some of you know, this week marks Share a Story - Shape a Future 2011. Each day bloggers around the world will write on a specific topic related to literacy. Today's topic is "The Gift of Reading" -- a subject that just happens to coincide with a post I've been planning for a while now, ever since I stumbled across this old photograph ...

That is my father, John Wheeler Auxier.[1. Please note that he is John and I am Jonathan ... a difference I cling to when accused of being a “jr.”] He’s reading Doctor DeSoto to me and my sisters. This was one of hundreds of books he read aloud to us, always using voices, always willing to indulge us with “just one more.”

All through elementary school, my father made regular visits to our classes to read aloud. He did this every week from first to sixth grade. This was not a luxury of time; during many of these years he was working two or three jobs to keep the family afloat -- all while trying to complete graduate school. Still, he always made time to read.[2. In fact, I would argue that reading aloud is one of few "advantages" a parent can give their child that doesn’t cost money.]

When I think about "the gift of reading," I picture my father standing before my class, caught up in a terrifying impression of Blind Old Pew or Jadis, the Last Queen of Charn. I remember watching him, proud and hopeful that I might one day be able to orate with such passion. I suspected then what I know now: it is not enough just to buy a kid a book. It is not even enough to let kids see you read. Reading must be relational. The difference between reading a stop sign and reading a book is that the latter is a conversation between the audience and storyteller. Everything else is just words on a page.

Even after I reached "reading fluency," my father continued to read aloud to me -- sharing books that were otherwise just out of reach. I was in fifth grade when he read Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes. Anyone who knows this book knows that it is a story meant to be handed down from father to son. The copy he read to me was a tattered first edition, stamped inside and out with the words "Property of John. W. Auxier" from when he was a boy. Of course, I didn’t understand everything I heard, but I understood enough to be thrilled. When he finished reading it, he gave the book to me, and I have re-read it every October since. Often aloud.

Even after I reached "reading fluency," my father continued to read aloud to me -- sharing books that were otherwise just out of reach. I was in fifth grade when he read Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes. Anyone who knows this book knows that it is a story meant to be handed down from father to son. The copy he read to me was a tattered first edition, stamped inside and out with the words "Property of John. W. Auxier" from when he was a boy. Of course, I didn’t understand everything I heard, but I understood enough to be thrilled. When he finished reading it, he gave the book to me, and I have re-read it every October since. Often aloud.

Ray Bradbury soon became my favorite author, and a few years later, my father took me to a writing convention to meet him in person. I only remember two things from that busy day. The first was when my father mentioned -- almost in passing -- that he thought I should be a writer. The second was something that happened at the end of the day:

Bradbury had finished his keynote address and was now signing books, battling off hundreds of eager fans all clamoring to meet him. My father, who had gone to the washroom, returned from the hall a moment later with a bemused smirk. "I just peed next to Ray Bradbury," he said.

A million things rushed through my mind -- among them the realization that Bradbury was, in fact, bound by the laws of nature. And imagine the luck! Hundreds of people were waiting in line for this man's signature, and my father got a private audience. "What did you say to him?" I asked, imagining what question I might have chosen.

He shrugged. "I told him 'Your signing-hand must be pretty sore.'"

I remember being in total awe: when faced with his childhood hero, my father had remained completely calm -- casual even. But looking back on that day, his reaction seems less shocking to me now.

After all, my father had been having conversations with Ray his whole life.

* * *

For those interested in other "Gift of Reading" stories, I highly recommend you check out BookDads, where Chris Singer has brought together dozens of bloggers to tell stories about fatherhood and the Gift of Reading. Then pick up a copy of Something Wicked This Way Comes and read it to someone.

"Who has more pockets than a magician?A boy. Whose pockets contain more than a magicians? A boy's."

- Ray Bradbury Something Wicked This Way Comes, ch. 49

I am not the biggest fan of Twitter. I can only get work done when my internet is disconnected, and the idea of a "community" that requires constant input is both daunting and distracting. Still, a few months ago I signed up ... and quickly discovered that I am the worst Twitterer in the world.[1. Of course, Charlie Sheen has since won this title out from under me]

Case in point: last week I wrote the following message --

With hindsight, I can see that this is a bit, shall we say ... desperate? At the time, however, I was simply thinking "Gee, people post these kinds of messages all the time and then get a zillion followers -- I want a zillion followers!" I hit "tweet" and waited for success.

So how many new followers did I get?

Zero. None. Not even a spambot. In fact, I lost a follower.[1. It was a Thai restaurant from Minnesota ... why they were following me in the first place, I'll never know.] If there's a moral to this story, it's something about how I should never again be allowed near a computer.

Despite the shattering of my fragile ego, there has been one big upside to using Twitter: I've made connections with a number of interesting people in the children's book world -- people I wouldn't have met otherwise. For example, Deer Hill Elementary teacher Mike Lewis reached out and invited me to contribute a video to his school's annual Read Your Heart Out Day (warning: contains me in pajamas).

Another example is Share a Story - Shape a Future 2011. This is an annual literacy event hosted by a variety of children's book bloggers. My involvement was slightly accidental. A few weeks back I answered a call for photos of writers' notebooks from teacher-blogger Sarah Mulhern. I sent her a few photos of my old journals. Little did I know what I was getting into. You see, Sarah's "author notebook" post is a part of a massive event that includes dozens of teachers/librarians/writers/book lovers all over the world. The theme this year is "Unwrapping the Gift of Literacy," and each day will tackle a different topic:

Another example is Share a Story - Shape a Future 2011. This is an annual literacy event hosted by a variety of children's book bloggers. My involvement was slightly accidental. A few weeks back I answered a call for photos of writers' notebooks from teacher-blogger Sarah Mulhern. I sent her a few photos of my old journals. Little did I know what I was getting into. You see, Sarah's "author notebook" post is a part of a massive event that includes dozens of teachers/librarians/writers/book lovers all over the world. The theme this year is "Unwrapping the Gift of Literacy," and each day will tackle a different topic:

MONDAY - The Power of a Book

TUESDAY: The Gift of Reading

WEDNESDAY: Unwrapping Literacy 2.0

THURSDAY: Keeping School from Interfering with the Gift of Literacy

FRIDAY: Literacy: The Gift that Keeps on Giving

Once I figured out (through Twitter, of course) what this event was, I asked if I could join the fun. The coordinators are nice people and said "dive in!" I'll be posting related pieces this Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday. In the meantime, check out posts about "the power of a book" at The Book Whisperer and Reading is Fundamental.

Perhaps the second greatest book dedication of all time: "For my parents. Obviously."

Adam Gidwitz, A Tale Dark and Grimm

Hey, folks! For the final of day "Peter Pan Week," we've got a special treat: Barrie scholar Kerry Mockler has written a post. Readers of The Scop might know Kerry better as "Kbryna," a regular commenter on this here blog and the woman behind The Moving Castle. Kerry wrote her master's thesis on The Little White Bird and is currently finishing a dissertation on Mr. Rogers at the University of Pittsburgh.[1. For those who have never been to Pittsburgh, it is worth noting that locals take their Fred Rogers very seriously.] Today she's agreed to share her thoughts about the most enigmatic character in all of Peter Pan ... the narrator! Take it away, Kerry:

* * *

We're used to thinking of Peter Pan as a symbol of perpetual childhood, of carefree innocence, joy, adventure, and freedom ... but Peter Pan also has nightmares. What we forget, or never knew in the first place, is that at its heart, all of Barrie's versions of Peter Pan are about loss and exclusion. That famous first sentence – "All children, except one, grow up" – sets up these themes, which also serve to close the novel. The loss of childhood (of one's own childhood and of one's child) finds expression throughout the novel, largely through the peculiarly ambivalent and enigmatic narrator. Exclusion and longing form -- for me, at least -- the strongest themes of the book, which make it one of the most melancholy stories I know. All those children, growing up, leaving behind Peter Pan who cannot grow up, and who masks his inability to grow up with the illusion of a defiant choice to remain a child.

Peter is not captain of the Neverland by choice, though he initially presents himself as an intentional runaway, defying the world that would have him grow up to be a man. Instead, he is marooned; when he tries to return to the home from which he has run away, "the window was barred, for mother had forgotten all about me, and there was another little boy sleeping in my bed." Thus he moves on to the Neverland, where he deals with lost children who all eventually outgrow their trees and their boy-leader. Peter's memory, a continual tabula rasa, prevents him from forming lasting relationships with anyone; even Tinker Bell, even Hook, are forgotten by the novel's end -- but the loss of that mother and that home are always with him.

The narrator of Peter Pan poses one of the biggest challenges to any reader; he attempts to identify with both child and adult, leaving us as readers in a linguistic and psychological muddle. The narrator’s inconsistency in using the first-person singular and first-person plural create confusion about his position in the text, and to whom he speaks: is he an adult addressing adults? or a child addressing adults? or an adult addressing both adults and children? He is never clearly one or the other, and never seems to manage to merge both into one adult/child hybrid; like Peter himself, the narrator is a "betwixt-and-between," neither one thing nor any other.[1. Upon returning to the Gardens in The Little White Bird, Peter is shocked to learn from the crow Solomon Caw that he is not still a bird, but more like a human — Solomon says he is crossed between them as a "Betwixt-and-Between."] The narrator's bitterness and unhappiness at his position is made clear at the end of the book, when the Darling children return home. Anticipating the reunion, the narrator says:

The narrator of Peter Pan poses one of the biggest challenges to any reader; he attempts to identify with both child and adult, leaving us as readers in a linguistic and psychological muddle. The narrator’s inconsistency in using the first-person singular and first-person plural create confusion about his position in the text, and to whom he speaks: is he an adult addressing adults? or a child addressing adults? or an adult addressing both adults and children? He is never clearly one or the other, and never seems to manage to merge both into one adult/child hybrid; like Peter himself, the narrator is a "betwixt-and-between," neither one thing nor any other.[1. Upon returning to the Gardens in The Little White Bird, Peter is shocked to learn from the crow Solomon Caw that he is not still a bird, but more like a human — Solomon says he is crossed between them as a "Betwixt-and-Between."] The narrator's bitterness and unhappiness at his position is made clear at the end of the book, when the Darling children return home. Anticipating the reunion, the narrator says:

"However, as we are here we may as well stay and look on. That is all we are, lookers-on. Nobody really wants us. So let us watch and say jaggy things, in the hope that some of them will hurt.”

The narrator’s exclusion from the homecoming scene echoes Peter’s exclusion from his own nursery. The narrator’s looking on from outside of the text recalls the image of Peter flying up to his old nursery window and finding it closed and barred. Watching the reunion of the Darlings, the narrator tells us:

“He had ecstasies innumerable that other children can never know; but he was looking through the window at the one joy from which he must be for ever barred."

Peter, of course, is not the only one to see the reunion; the narrator looks on as well and speaks for them both as he narrates the one joy from which both he and Peter are barred. As Hook and Mr. Darling are twinned, so too are Peter and the narrator. At the end, they are the only two who remain: Wendy grows up and Mrs. Darling dies, forgotten. The cycle of little girls to do the spring-cleaning goes on and on, but Peter and the narrator remain alone, excluded, untouched by time.

* * *

On that poignant note, we come to the end of "Peter Pan Week." While researching topics, I came across some great stuff I couldn't fit into posts -- including a few pretty hilarious Pan-related image macros, an incredibly disturbing headline, and a scathing review of Lars von Trier's offbeat movie adaptation. You should all count yourselves lucky that I didn't make it "Peter Pan MONTH." Now that would be an awfully big adventure.

For those who missed the other "Peter Pan Week" posts:

Day One: Literary Dress Rehearsals

Day Two: The Problem with Peter

Day Three: Tink or Belle?

Day Four: The Neverland Connundrum

Also, you can also read my ham-fisted attempt to connect Peter Pan to The Hunger Games here.

"Neverland had always begun to look a little dark and threatening by bedtime. Then unexplored patches arose in it and spread, black shadows moved about in them, the roar of the beasts of prey was quite different now, and above all, you lost the certainty that you would win."

-J.M. Barrie Peter Pan, ch. IV

While discussing Peter Pan with my students last week, we found ourselves in a debate about the nature of magic in the book. On one hand, it seems like all magic comes from Peter Pan -- he seems almost able to control the island and its inhabitants with his very thoughts. On the other hand, the Neverland[1. I love that Barrie uses an article in front of "Neverland" ... I just sounds cooler.] occasionally seems to operate with an intelligence and power all of its own. There's a chilling moment as they approach the island that speaks to this disconnect:

"They had been flying apart, but they huddled close to Peter now. His careless manner had gone at last, his eyes were sparkling, and a tingle went through them every time they touched his body. They were now over the fearsome island, flying so low that sometimes a tree grazed their feet. Nothing horrid was visible in the air, yet their progress had become slow and laboured, exactly as if they were pushing their way through hostile forces. Sometimes they hung in the air until Peter had beaten on it with his fists.

'They don't want us to land, he explained.

'Who are they?' Wendy whispered, shuddering.

But he could not or would not say.

So who's in charge, Peter or the Neverland? People who have been reading The Scop all week may have a guess as to where this is going: I think Barrie's refusal to answer that question is a part of what makes Peter Pan so wonderful. When a writer chooses ambiguity, he places the task of knowing The Answer on the reader -- and instantly turns the book into a conversation.

At least, that's usually how it works. But I'll admit that there's something about this contradiction that feels more frustrating than others in the book. I think that's because it has to do with the rules of the world. By all means, make your characters and events ambiguous, but please be specific about the spaces those characters inhabit. I'm reminded of something screenwriter Blake Snyder talks about in his book, Save the Cat! He mentions the problem of "Double Mumbo-Jumbo" -- the idea that audiences will only accept one piece of magic per movie. (Or, as Snyder puts it: "You cannot see aliens from outer space land in a UFO and then be bitten by a Vampire and now be both aliens and undead.")[2. Obviously, this rule does not apply to Holly Black and Justine Larbalestier.]

This "double mumbo-jumbo" is something I see in a lot of books and movies, and it bothers me quite a bit. I've read Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes every October for the last fifteen years; over that time, I've become aware that the book contains, not one, but two magical forces: the Dust Witch and the carousel.[3. While we're talking about magic carousels, I've always thought Cornelia Funke's The Thief Lord commits this very same infraction ... only in that case it's less a question of "double mumbo-jumbo" than "double plot convenience."] The problem with these competing forms of magic is that they ask too much of the audience too late into the story. Even worse, the lack of clarity about the world erodes our faith in the author, meaning we do not engage the way we should.

This "double mumbo-jumbo" is something I see in a lot of books and movies, and it bothers me quite a bit. I've read Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes every October for the last fifteen years; over that time, I've become aware that the book contains, not one, but two magical forces: the Dust Witch and the carousel.[3. While we're talking about magic carousels, I've always thought Cornelia Funke's The Thief Lord commits this very same infraction ... only in that case it's less a question of "double mumbo-jumbo" than "double plot convenience."] The problem with these competing forms of magic is that they ask too much of the audience too late into the story. Even worse, the lack of clarity about the world erodes our faith in the author, meaning we do not engage the way we should.

So here, at last, may be an honest to goodness flaw in Peter Pan. I have to admit that part of me feels relieved.

* * *

For those who missed the other "Peter Pan Week" posts:

Day One: Literary Dress Rehearsals

Day Two: The Problem with Peter

Day Three: Tink or Belle?

Day Five: Loss and Exclusion in Peter Pan (special guest post!)

Also, you can also read my ham-fisted attempt to connect Peter Pan to The Hunger Games here.

The Website of Jonathan Auxier

Hi, I'm Jonathan!

I write strange stories for strange kids. This is my website, where I talk about children's books old & new.

In stores now!

The long-awaited conclusion to the VANISHED KINGDOM series!

The War of the Maps is a breathtaking fantasy in the vein of His Dark Materials and The Last Battle that dares to give new answers to age-old questions—inviting readers of all ages to sail beyond the edges of the map into a world of magic, myth, and boundless adventure.

Since time before time, two opposing forces have been locked in an endless battle: It is the war between magic and reason—between what if and what is. And the victor will not just shape the future but the very nature of reality.

Available for in stores now!

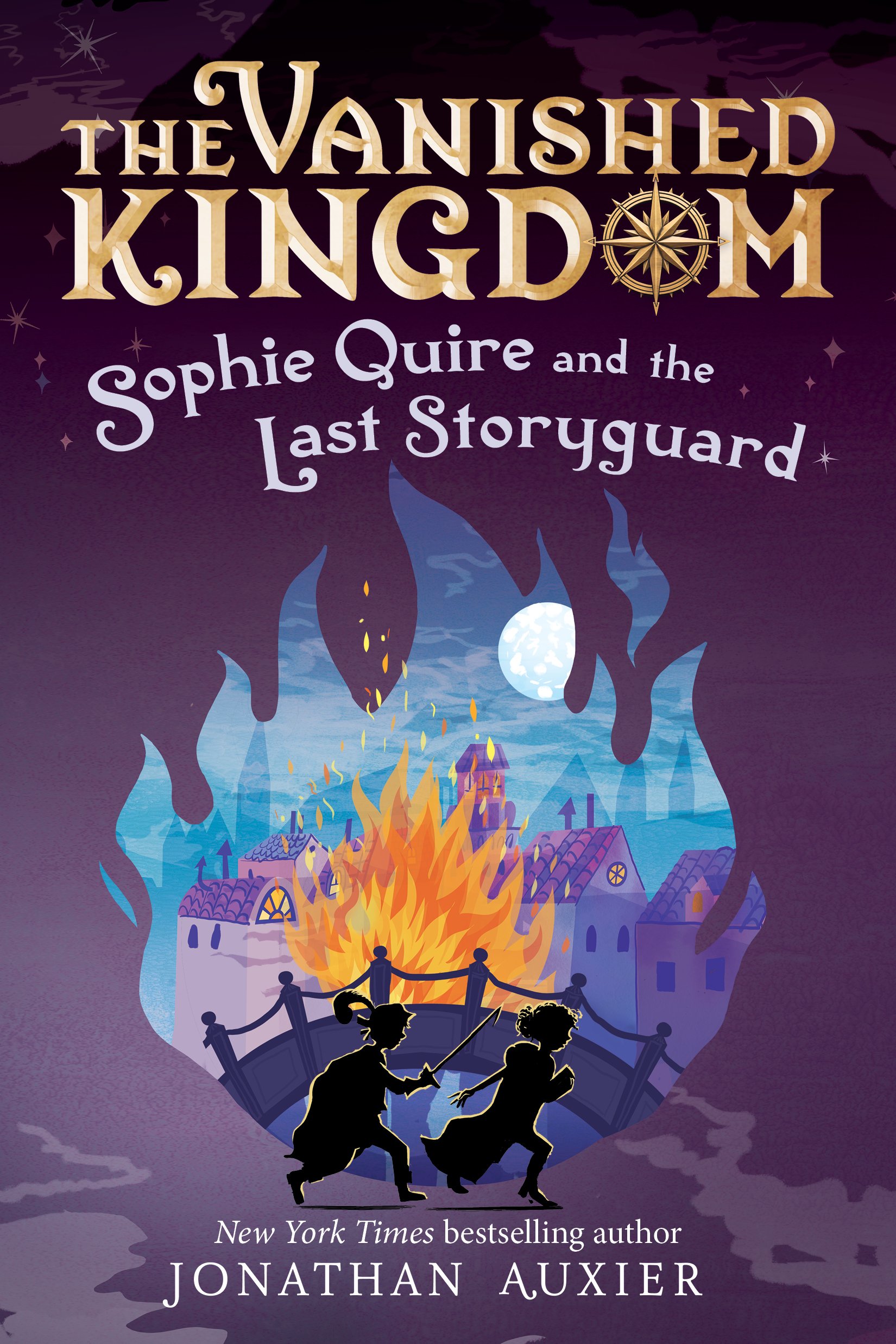

The heart-racing second book in the VANISHED KINGDOM series. It’s been two years since Peter Nimble and Sir Tode rescued the kingdom of HazelPort. In that time, they have traveled far and wide in search of adventure. Now they have been summoned by Professor Cake for a new mission: To find a twelve-year-old bookmender named Sophie Quire. Sophie knows little beyond the four walls of her father’s bookshop, where she repairs old books and dreams of escaping the confines of her dull life. But when a strange boy and his talking cat/horse companion show up with a rare and mysterious book, she finds herself pulled into an adventure beyond anything she has ever read.

You can learn more and read some starred reviews here … or check out the first few chapters for free!

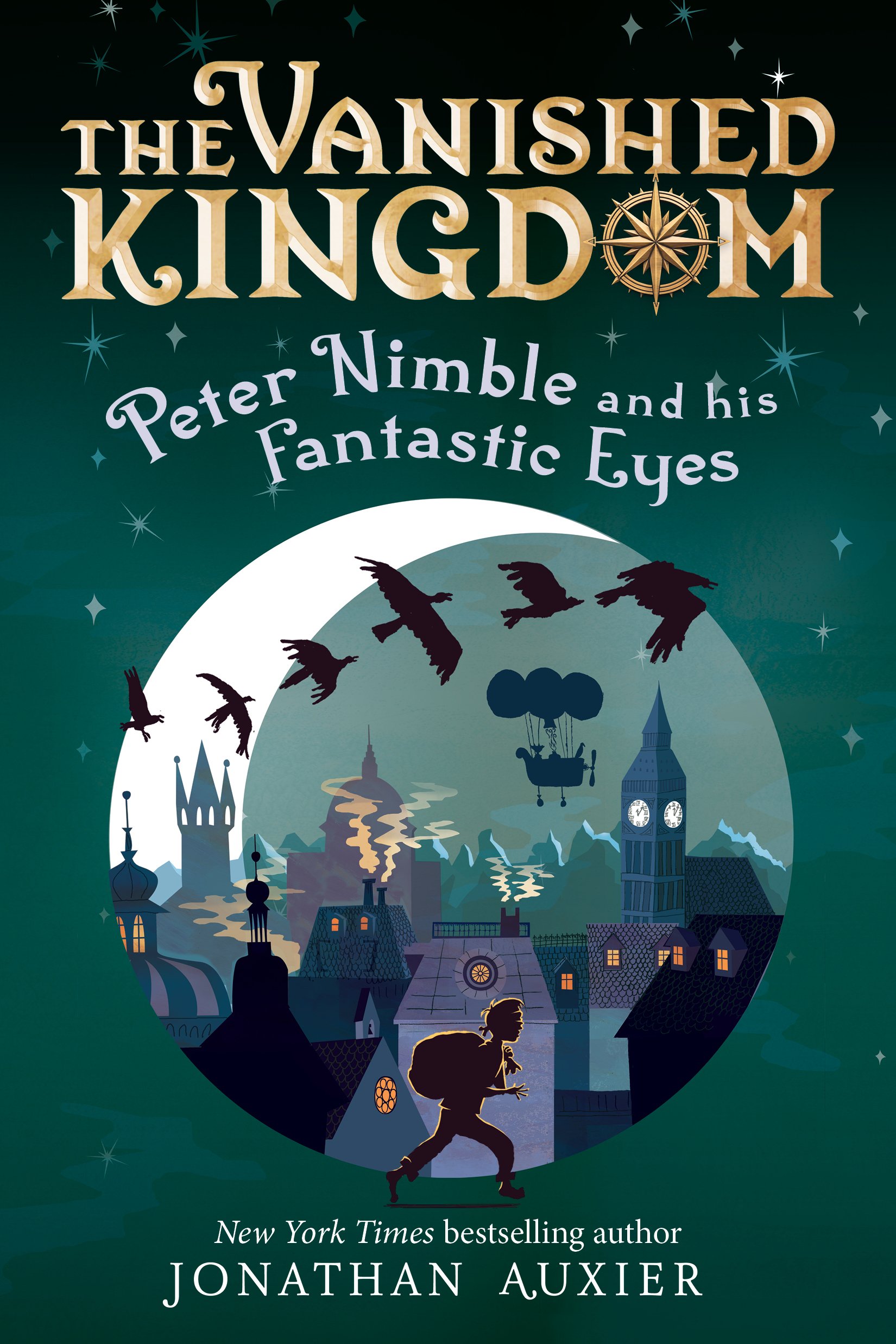

The first thrilling book in the acclaimed VANISHED KINGDOM series. The epic journey of a small, blind orphan ... who also happens to be the greatest thief who ever lived!

Peter Nimble was an ABA New Voices pick, an Indie Next List Selection, and Bookpage magazine Best Book of the year! It won the Paterson Poetry Prize, The Diamond Willow Award, and an MYRCA Honor. It was shortlisted for: the Monica Hughes Award, the Sequoyah Award, Massachusetts Children’s Book Award, The Blue Hen Literary Award, and the Canadian Children’s Book Award.

Visit PeterNimble.com for games and more info. Read the first chapter for free! Or read some reviews here. Or watch the book trailer!

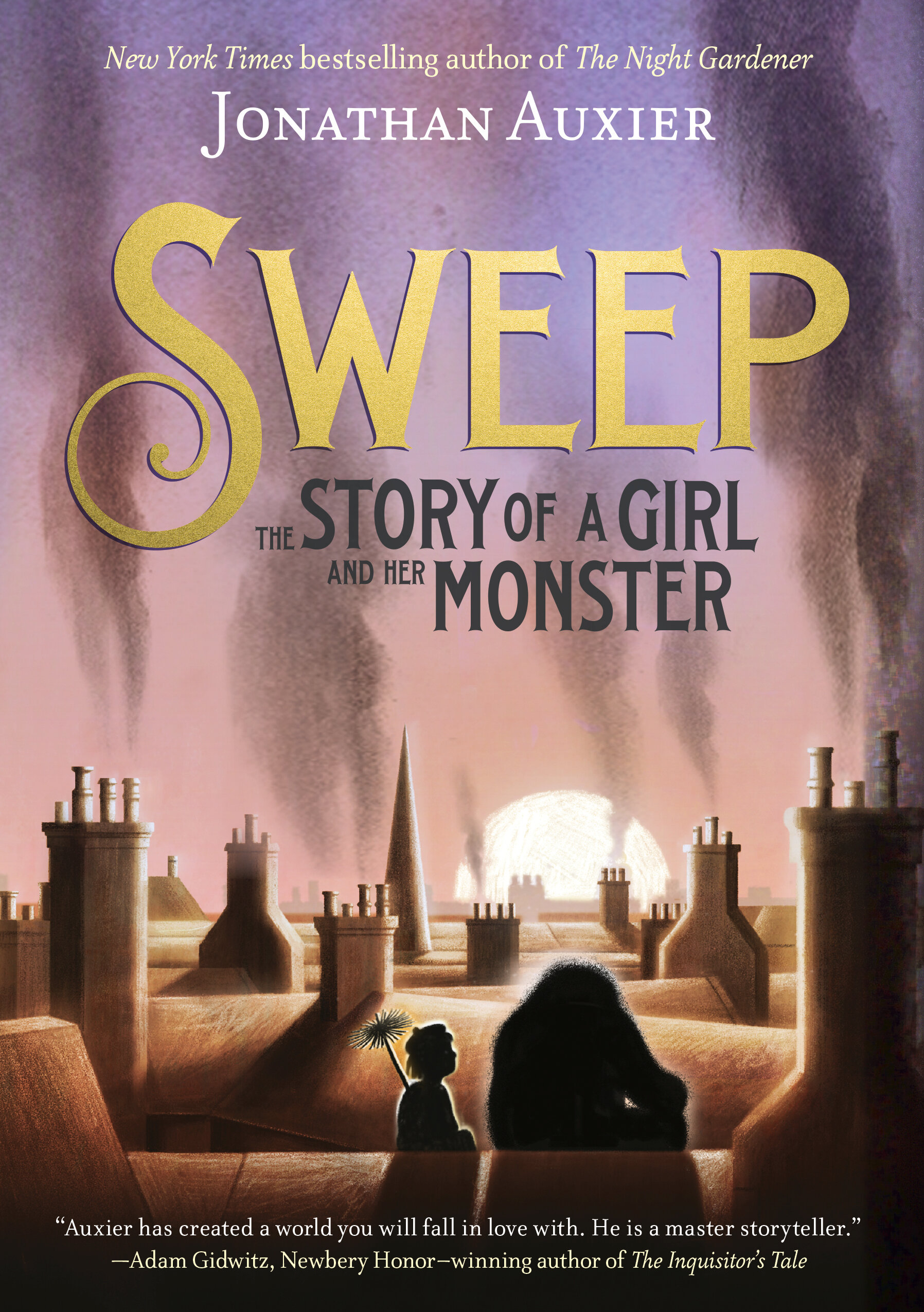

It's been five years since the Sweep disappeared. Orphaned and alone, Nan Sparrow had no other choice but to work for a ruthless chimney sweep named Wilkie Crudd. She spends her days sweeping out chimneys. The job is dangerous and thankless, but with her wits and will, Nan has managed to beat the deadly odds time and time again. When Nan gets stuck in a chimney fire, she fears the end has come. Instead, she wakes to find herself unharmed in an abandoned attic. And she is not alone. Huddled in the corner is a mysterious creature—a golem—made from soot and ash.

Sweep is the story of a girl and her monster. Together, these two outcasts carve out a new life—saving each other in the process. Sweep received six starred reviews and was the winner of the Governor General’s Award and the Sydney Taylor Book Award.

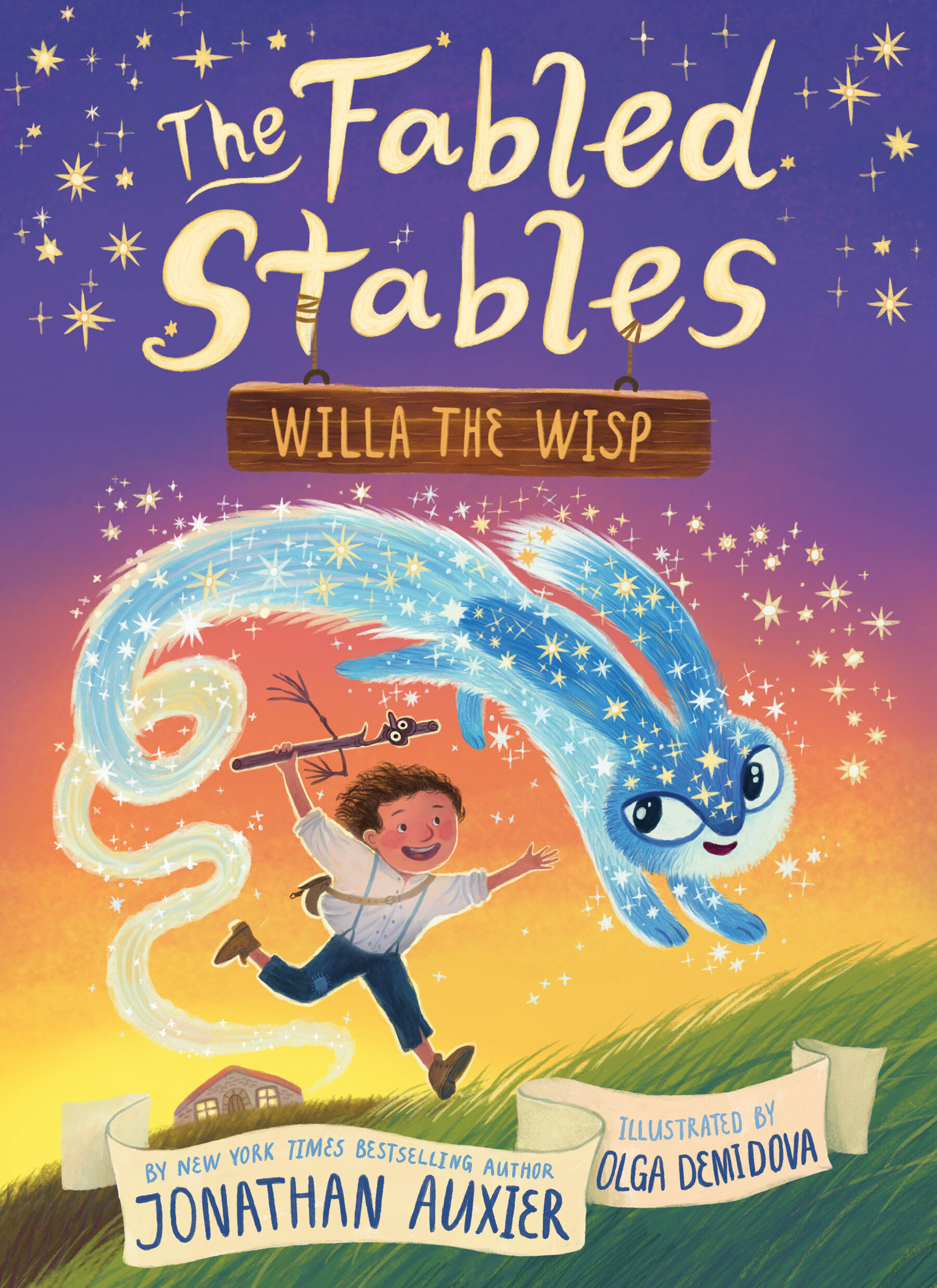

Welcome to the Fabled Stables, a magical building filled with one-of-a-kind creatures. Creatures including the Gargantula, the Yawning Abyss, the Hippopotamouse . . . and Auggie. Auggie is the only human boy at the Stables, and he takes care of all the other animals. The Fabled Stables have a mind of their own, and every so often, the building SHAKES and SHUDDERS, TWITCHES and SPUTTERS—it’s making room for a new arrival! It’s Auggie’s job to venture out and rescue a new creature from mortal danger. But will he be able to complete his mission before it’s too late? With some help from Fen (a literal stick-in-the-mud) and his animal companions, Auggie saves the day and makes a new friend in the process.

A thrilling, silly new series packed full of stunning full color illustrations by Olga Demidova. The Fabled Stables received STARRED reviews from Kirkus and Publisher’s Weekly and was named by Amazon as a Best Book of 2020. Available at your awesome local indie!

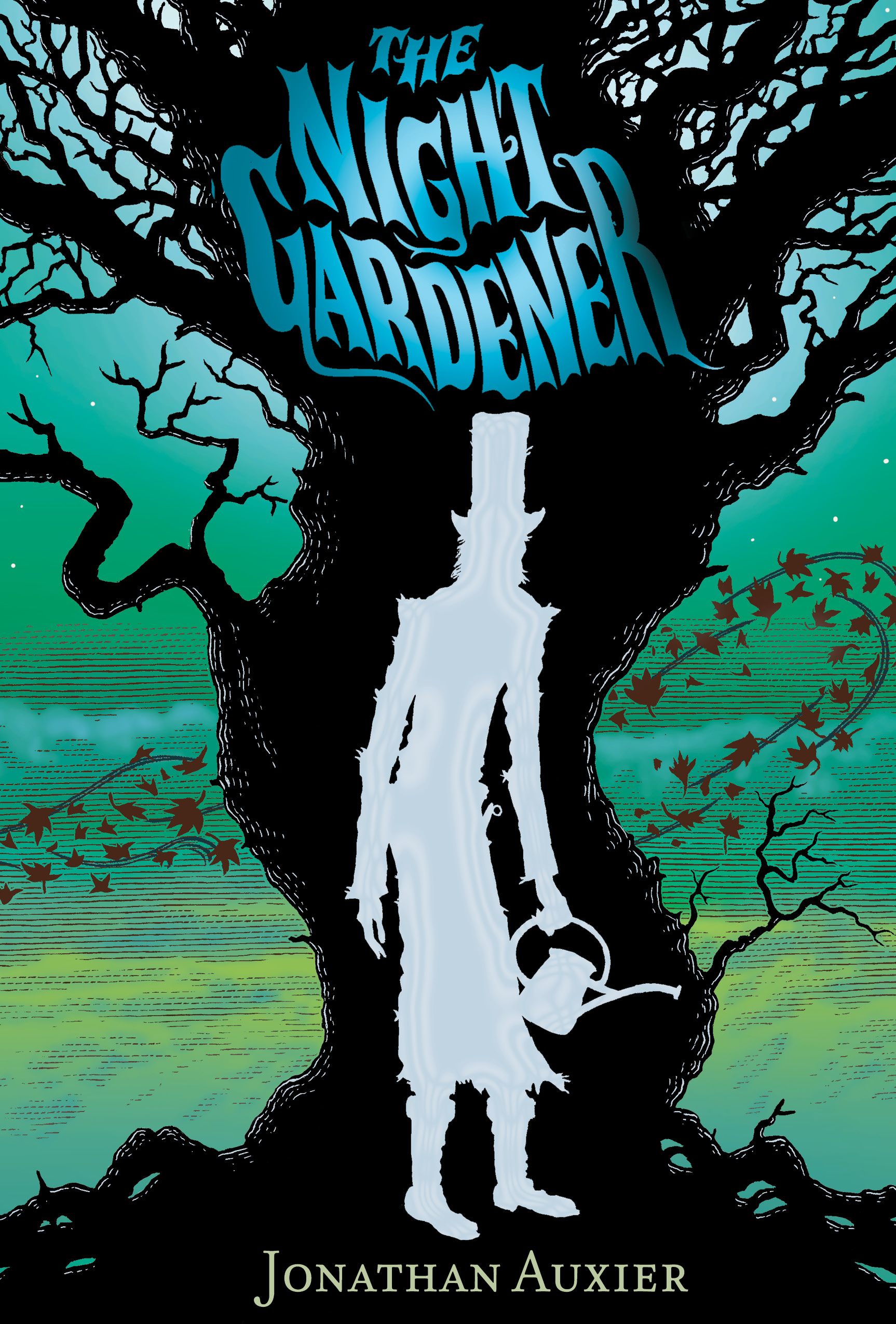

A chilling ghost story about two abandoned Irish siblings who travel to work as servants at a creepy, crumbling English manor house. But the house and its family are not quite what they seem. Soon the children are confronted by a mysterious spectre and an ancient curse that threatens their very lives. More than just a spooky tale, it’s also a moral fable about human greed and the power of storytelling.

The Night Gardener is a New York Times bestseller, a Junior Library Guild Selection, Amazon “Best Book” for May 2014, and an ABA “Indie Next” pick. It received five starred reviews and won the ILA Book Award! You can read more reviews here.

Powered by Squarespace.