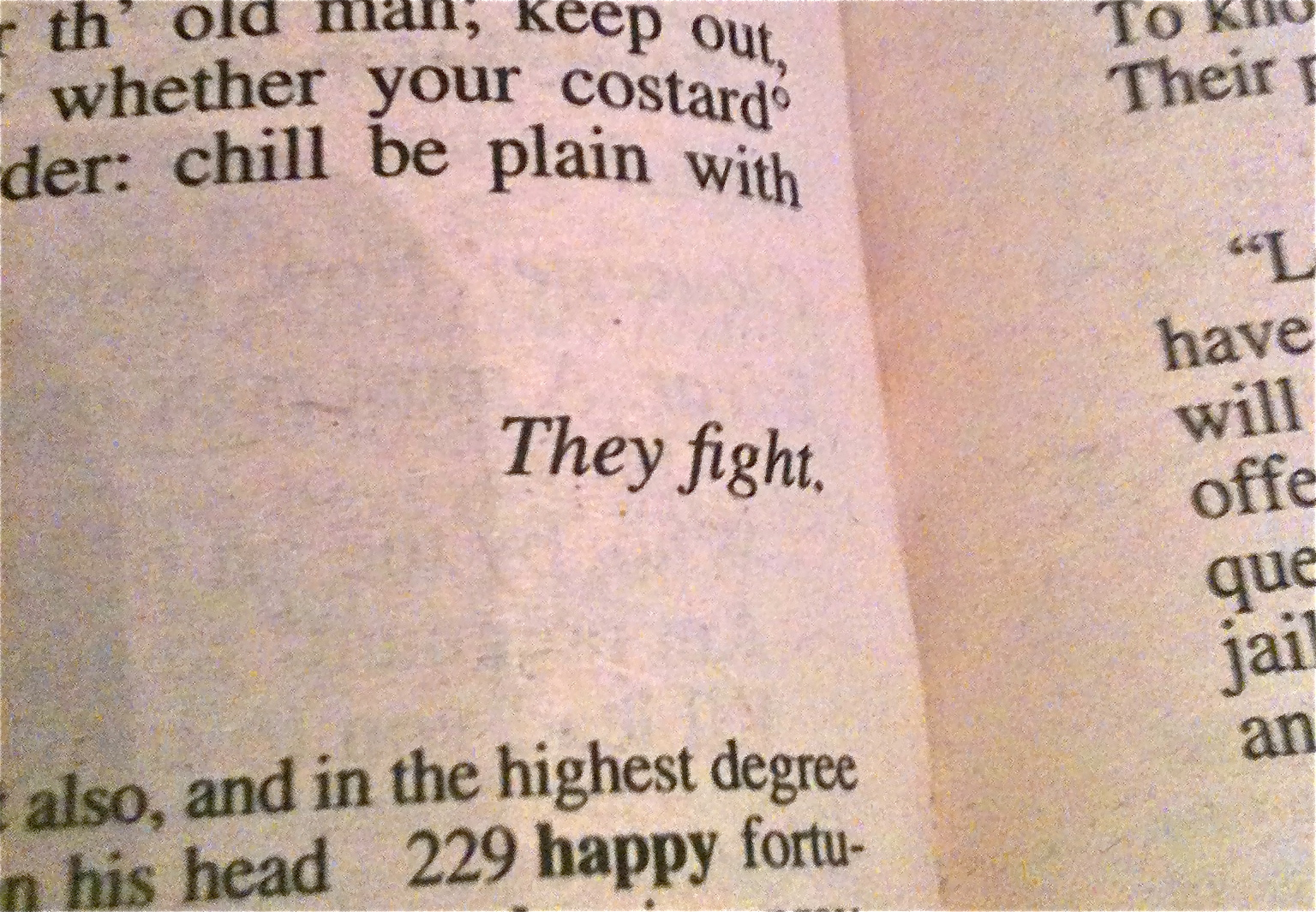

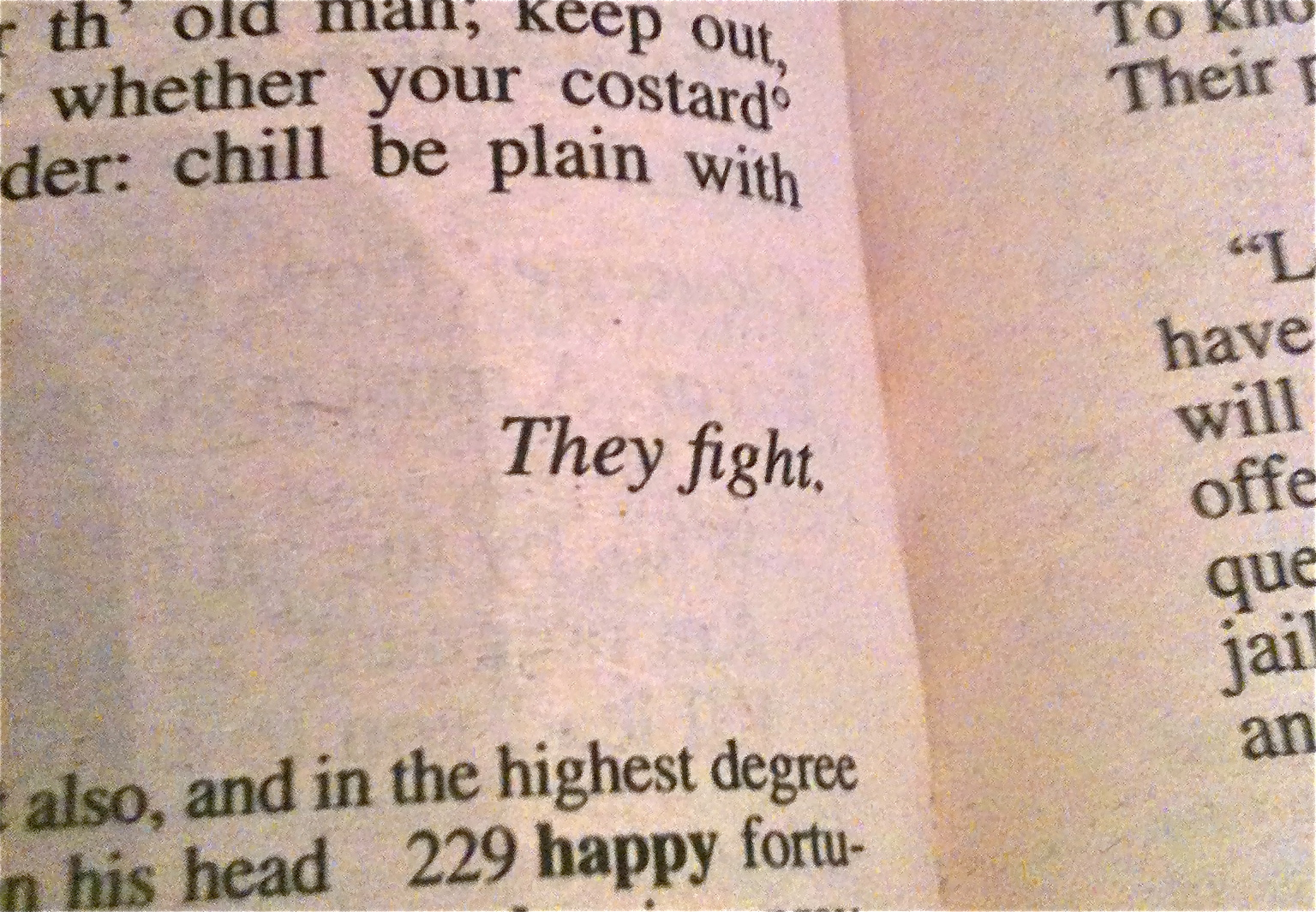

In theatre, descriptive action sequences are almost non-existent. Hamlet may talk a big game, but at the end of the script, all we get is: “dies” (Not even a definite article for the poor Prince of Denmark!) This works in playwriting because specific action is limited to the capabilities of specific actors, budgets, and stages -- why write a death scene that a director will just have to change anyway?[1. One could argue that the unique appeal of theatre is this infinite variety in staging possibilities -- no two productions are alike.]

The same is not true for novelists and screenwriters. Books and movies are stories fixed in time -- if every reader is seeing a different thing during an action scene, that’s a problem.[2. I am not objecting to ambiguous ideas or themes in books and movies, but I would argue that the basic questions who/what/where/when should be universally understood … because only when those things are clearly established can readers effectively debate the why behind those actions.] Unfortunately, I often read action sequences that give me the feeling that writers are going on autopilot: instead of writing a tightly constructed series of dramatic events, they simply write “and here we get an awesome chase sequence!”

I’m ashamed to say I’ve done it myself. Writing action scenes is hard, and it’s nice to think that those difficult bits can be reduced to a few lines of summary. But summarizing fights and chases is like a comic carefully setting up a joke and then replacing the punch line with “hilarity ensues!" (To be fair, "hilarity ensues" is sort of an awesome punch line in its own right.)

I’m ashamed to say I’ve done it myself. Writing action scenes is hard, and it’s nice to think that those difficult bits can be reduced to a few lines of summary. But summarizing fights and chases is like a comic carefully setting up a joke and then replacing the punch line with “hilarity ensues!" (To be fair, "hilarity ensues" is sort of an awesome punch line in its own right.)

And when you get down to it, truly funny moments don’t even have traditional punch lines -- watch your favorite comedy and write down the laugh-out-loud moments. I guarantee you that the biggest laughs will fall on generic lines like “Actually I quite like it” and “I can imagine.”[3. These are actual examples taken from Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy ... I find such human moments far funnier than the digressions on multiple heads and improbability engines.] Such lines are not funny in a vacuum; they’re funny because that character said it in that specific moment.[4. This is something my MFA director Milan Stitt was fond of saying -- credit goes to him for the observation.]

I'm going to make a confession that I might regret. About a year ago, I joined some of Mary's colleagues in a weekly "tabletop gaming" group ... which is a dressed-up term for Dungeons & Dragons. This was a pretty smart bunch of people (our game master has a PhD in comic books!), and I learned a lot from the experience -- not only about roleplaying games, but also about the give-and-take of corporate storytelling.

One of the central aspects of any roleplaying game is combat. Generally speaking, most roleplaying games are pretty conversational and free-form … but when a bad guy shows up, everyone pulls out dice, and charts, and (in my case) a calculator! Suddenly, there's an order of operations, and a series of rigid rules to help choreograph every movement of a battle.

I sort of became obsessed with the details of these "encounters" and started taking copious notes about every move in the hope of unlocking some secret about how to write action scenes. I wanted to figure out what separated the so-so encounters from the ones that sucked us in -- inspiring recaps, arguments, and in-jokes.

What I discovered is that blow-by-blow, the actions in a fun encounter were no different from those in a boring encounter -- sometimes you landed a hit, sometimes you missed. What made a difference was when those ordinary actions were a reflection of the personality of individual character: a hothead fighter dives into a suicide battle right after the rest of the group has agreed to retreat; a vengeful character murders an enemy who has already surrendered; a noble character sacrifices herself so that others can escape.

That is to say, the actions are dramatic because that character did them in that specific moment.