Plot vs. Story in THE CHOCOLATE WAR

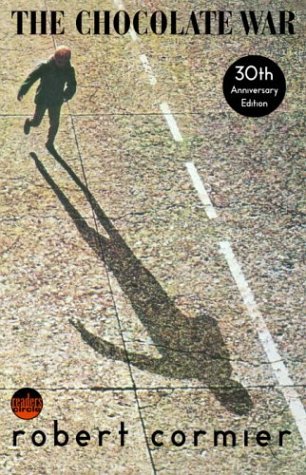

/ Last week in our Children's Literature course, Mary and I discussed Robert Cormier's proto-YA novel The Chocolate War (1974). For those who have not read it, The Chocolate War is a harrowing story of a freshman who dares to buck convention by refusing to participate in the school-wide chocolate sale. This book was a perfect followup to William Golding's Lord of the Flies. In some ways, The Chocolate War is a continuation of Flies' thesis about the depravity of human nature, but unlike the earlier book, The Chocolate War does not seek shelter in rules and law -- in fact, social strictures are depicted as fundamentally destructive.

But that's not what I want to talk about today. Today I want to talk about a unique way that Robert Cormier achieves a sense of "interiority" in his writing. YA literature is often noted for its use of interiority -- working overtime to forge a direct, emotional connection between reader and protagonist. We don't just know what the main character did, we know how they felt while they were doing it. (This probably explains why so many adolescent girls are in love with Holden Caulfield.)

Last week in our Children's Literature course, Mary and I discussed Robert Cormier's proto-YA novel The Chocolate War (1974). For those who have not read it, The Chocolate War is a harrowing story of a freshman who dares to buck convention by refusing to participate in the school-wide chocolate sale. This book was a perfect followup to William Golding's Lord of the Flies. In some ways, The Chocolate War is a continuation of Flies' thesis about the depravity of human nature, but unlike the earlier book, The Chocolate War does not seek shelter in rules and law -- in fact, social strictures are depicted as fundamentally destructive.

But that's not what I want to talk about today. Today I want to talk about a unique way that Robert Cormier achieves a sense of "interiority" in his writing. YA literature is often noted for its use of interiority -- working overtime to forge a direct, emotional connection between reader and protagonist. We don't just know what the main character did, we know how they felt while they were doing it. (This probably explains why so many adolescent girls are in love with Holden Caulfield.)

It's no surprise that The Chocolate War -- a seminal work of YA literature -- trades in interiority. But what is surprising is how the book goes about creating it. Generally speaking, most books aiming for interiority make use of the first-person narrative mode.[1. Some go one further and employ the present-tense. If you like hearing people dump on contemporary literary conventions, I urge you to read Philip Pullman's delightful takedown of this trend.] As a writer, I'm a bit leery of this technique. Sure, a great number of brilliant novels have been written in the first person. But I also feel that less talented authors sometimes use this device to compensate for an anemic narrative. Most of the Twilight books contain about 100 pages of plot sandwiched between 500 pages of, er, "interiority."

Robert Cormier was a journalist, and it shows in his clean prose. Authors who rely too heavily on first person narration should feel shame when reading The Chocolate War, which somehow creates intimacy between reader and hero without ever ever breaking from the third person. Even more, Cormier doesn't even bother to stay with his protagonist in every chapter -- instead he nimbly hops from one side-character to another, shifting his third-person-limited perspective every few pages. In fact, every public scene containing the protagonist (Jerry Renault) is narrated from the perspective of an outside observer, and it's only after school that we get to hear out hero's take on the events that transpired. I would judge that at most 1/4 of the book is told from Jerry's POV, and yet, by the end, we somehow know him like a flesh-and-blood friend.

How does Cormier pull it off? I've read the book three times in as many months and still can't answer that question. However, on this most recent reading, I started to wonder if Jerry's aloofness was actually part of the puzzle. Perhaps the reason that we connect with Jerry so much is because we long to connect with him, and so when we do get a rare glimpse inside his head, we make the most of it.

My former writing teacher Milan Stitt once outlined the difference between "plot" and "story." He defined plot as the chronological list of events that transpire. Story is the act of telling those events in a way that creates meaning. These are two very different skill sets, and while the ability to concoct engaging plots is helpful, it is secondary to the ability to tell those events in a way that pays off. The gap between plot and story is the reason your mom can't retell a joke.[2. I see now that this comes dangerously close to a "your mom" jab ... Please accept my heartfelt apologies, Moms of the World.]

My former writing teacher Milan Stitt once outlined the difference between "plot" and "story." He defined plot as the chronological list of events that transpire. Story is the act of telling those events in a way that creates meaning. These are two very different skill sets, and while the ability to concoct engaging plots is helpful, it is secondary to the ability to tell those events in a way that pays off. The gap between plot and story is the reason your mom can't retell a joke.[2. I see now that this comes dangerously close to a "your mom" jab ... Please accept my heartfelt apologies, Moms of the World.]

Cormier understood that a book about selling chocolates would not work unless he made it meaningful ... unless he made it a story.[3. Robert Cormier died in November 2000, and Publisher's Weekly released this touching memorial discussing the man and his work.] Many people have observed that DIARY OF A WIMPY KID's Greg Heffley is a sort of middle-grade version of Holden Caulfield ... I wonder if there's a middle-grade version of Jerry Renault out there? Any ideas?